29 May 2023

After finishing the Fossil Discovery Trail, I felt as if I had walked not only through a landscape, but through time itself. The trail is 2.9 kilometers long and runs one way, cutting through a sequence of tilted rock layers that quietly expose their age and origin. These rocks hold stories from roughly 163 million to 95 million years ago, and walking among them felt like moving through pages of a very old, very patient book.

The trailhead begins just behind the Visitor Center. At first, the path follows the side of a low hill, leading through familiar desert scenery. The air was dry and clear, and the ground was pale and dusty, broken by scattered shrubs and cacti. To my right, the open desert stretched away in muted browns and greys. To my left, a rock wall rose close to the trail, its surface rough and fractured, colored in soft tans and reddish tones. The walking was easy, almost meditative, and for the first half mile the landscape felt quiet and restrained, as if it was preparing me for what was to come.

Gallery I: Opening desert and dramatic change of the landscape

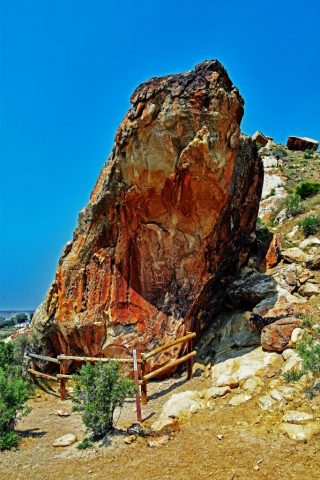

After this initial stretch, I reached the point where the trail turns up into a narrow canyon toward the quarry. Here, a large boulder sits beside the path, its surface washed in deep purples, reds, and warm gold. When I stepped closer, I noticed petroglyphs carved into the stone. They were subtle and easy to miss, but once seen, they anchored the place not only in geological time, but also in human history. This quiet meeting of rock, art, and silence felt deeply grounding.

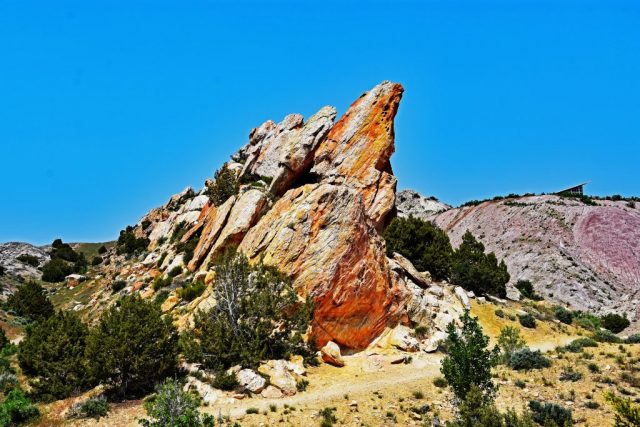

From there, the trail turned into a small valley, and almost immediately the scenery became more dramatic. The walls of the valley rose higher, and the colors intensified. Rock formations unfolded in layers of purple, orange, pale white, and golden red. Some rocks leaned sharply, tilted at striking angles, as if frozen in the middle of a slow collapse. Others stood like fins or folded waves, stacked one behind another. The light caught the edges and ridges, creating sharp contrasts between glowing surfaces and deep shadows.

About a quarter mile farther up the valley, I came to a cliff formed by the Morrison Formation. This was one of the key fossil areas along the trail. Dinosaur bones and ancient clams were exposed in the rock face, still embedded in their natural position, just as Earl Douglass had first found them in 1909. They were not obvious at first glance. I had to stop, slow down, and really look. Once my eyes adjusted, I began to recognize shapes and textures that did not belong to ordinary stone. Still, I must admit that I enjoyed the rock formations themselves even more than the fossils. The scale, color, and strange geometry of the landscape held my attention completely.

Gallery II: The rock formations dominate my eyes

Eventually, the quarry building came into view, perched above the valley. From the outside, it appeared modest, but stepping inside revealed an entirely different scale of time and life. On the upper level, a long, high wall was covered with bones, scattered yet purposeful, as if the rock itself had opened to reveal its contents. Femurs, ribs, vertebrae, and fragments of skeletons stretched across the wall, each one still partially embedded in stone.

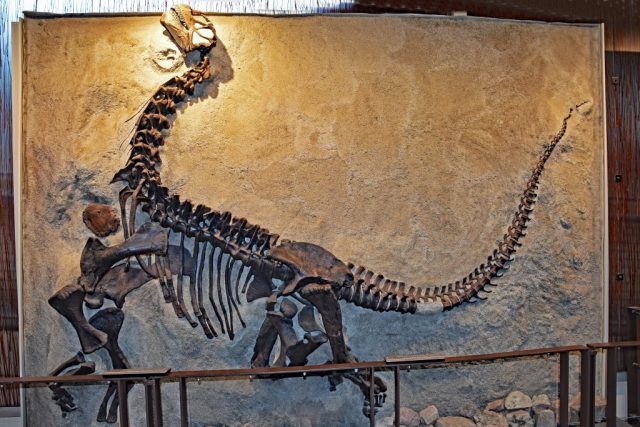

On the lower level, entire dinosaur skeletons stood assembled. One of the most striking was a young Camarasaurus, a long-necked herbivore belonging to the group known as sauropods. This species was the most common dinosaur in the Carnegie Quarry and the Morrison ecosystem around 149 million years ago. Seeing the full length of its neck and the massive curve of its body made it easy to imagine how dominant and yet strangely gentle these animals must have seemed in their time.

Nearby stood the skeleton of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a meat-eating dinosaur and the dominant predator of the Jurassic Period. Its posture and skull carried a sense of tension and movement, as if it could step forward at any moment. The contrast between predator and herbivore, displayed in the same space, gave the room a quiet intensity.

Gallery III: Inside the building, the quarry experience lingers visually

After I had seen enough, I stepped back outside into the sunlight. The valley lay quiet again, the rocks unchanged, indifferent to the millions of years they had already witnessed. I left the building and, rather than walking back, accepted a lift down to my car. As we drove away, the tilted layers of rock slipped past the window, and I felt a deep sense of calm, as if the trail had gently stretched my sense of time and then released it again.