13 September 2025

The morning air in Waterton carried the crispness of early autumn as I set off along the Rowe Creek Trail toward the lakes. The path rose steeply at once, climbing through the blackened trunks of a burnt forest. Charred stems stood like solemn reminders of fire, but between them tender green shoots and shrubs had returned, offering a striking contrast of destruction and renewal.

After the first sharp ascent, the grade eased, and my steps found a rhythm beside the burbling of Rowe Creek. The water’s sound kept me company as I walked beneath a canopy that gradually shifted from ghostly black to living green.

It was not long before the first mountain announced itself. Ahead and slightly to the left rose Ruby Ridge, exactly as its name suggests: a crest of deep maroon argillite, glowing even under a muted sky. Its slopes were jagged, ribbed with loose scree, and the red rock seemed to shift colour with the light—wine-dark in shadow, rusty orange where the sun struck its flanks. I felt sure this was Ruby Ridge, and later I learned I had guessed correctly.

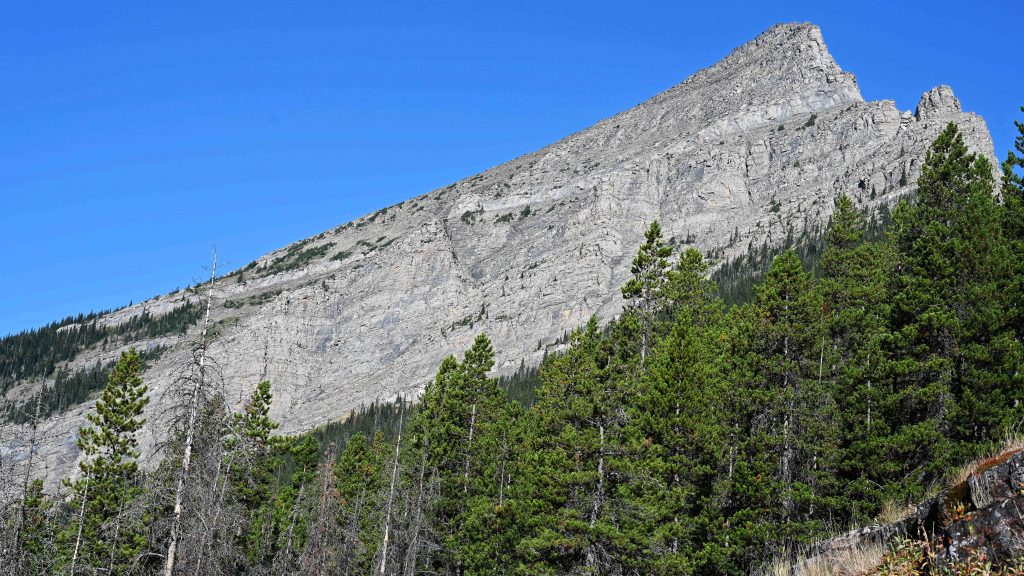

Higher and more massive behind it loomed Mount Blakiston, the park’s tallest peak. Where Ruby Ridge appeared sharp and crimson, Blakiston was austere and grey, its cliffs rising like fortress walls. The mountain seemed to carry a gravity of its own, dominating the skyline with a sheer, uncompromising face that dwarfed the ridges around it.

The trail wound gently, leading me deeper into the valley. About three kilometres in, a sudden rustle ahead startled me—there was a bear. For a fleeting moment, I watched him slip away into the brush, too quickly for my camera, leaving only the adrenaline in my chest. From that point, I shortened the distance to a couple walking ahead, from a hundred metres down to barely ten. The wilderness had reminded me of its presence.

Beyond the creek, the views opened wider, and another mountain came into sight on the right: Mount Lineham. Its profile was blocky, its layers painted in bands of colour—reddish stone low on the slopes, darker greys and purples higher up, and pale green touches where hardy plants had taken root. Later in the day, as light shifted, the rock glowed with a hint of orange, like embers cooling after a fire.

Closer to the lakes, to my left, rose the broad-shouldered Mount Rowe. Its ridge was less jagged than Ruby Ridge, more sweeping and rounded, but the red argillite still showed through in patches. Green slopes clung to its base, but higher up it grew bare, austere, a mountain stripped to its bones.

The final kilometre steepened again, pulling me upward through open meadows, until at last the panorama unfolded. Before me stretched Lineham Ridge, running away like a spine, its sides steep and sheer. The rock here was mottled—pinkish and rust-red where weathered, darker grey in shadow, streaked with thin black bands.

Below, the Rowe Lakes mirrored the sky, still and green.

To the left of the ridge stood Mount Alderson, a hulking massif whose broad faces bore the muted colours of sedimentary stone: grey, tan, and earth-brown, more uniform than the flamboyant red ridges I had passed. Farther along, glimpsed in the distance, was Mount Hawkins, dark in shadow, rugged but less commanding than Blakiston.

The afternoon light softened as I lingered at the viewpoint. Reds deepened into wine, greys into blue shadow, and the peaks seemed to settle into quiet repose.

I sat there for a while, the drama of fire-scarred valleys below and the raw splendour of mountains all around, before beginning the return.