October 20th, 2025

The morning sun greeted me with a deep blue sky, clear and wide over the Utah desert. The air was cool, still touched by the chill of the night, but already promising warmth for the day ahead. I made myself breakfast and coffee, the smell of it rising in the quiet air, before setting off from Upper Dry Creek toward the end of the Hole-in-the-Rock road — that legendary route carved through sandstone by determined settlers nearly a century and a half ago.

The landscape soon began to unfold in all its rugged glory. The mountains around me were not the soft, forested kind, but vast, bare formations of stone — sculpted by wind, water, and time. Their surfaces glowed in hues of red, orange, and gold, the morning light brushing their edges with soft shadows. Some cliffs rose like giant cathedral walls, others broke into smaller ridges and rounded domes, all of them shaped with an almost artistic precision by nature’s patient hand.

I stopped several times to take pictures. Every bend of the road revealed another breathtaking view — layers of rock that seemed to tell ancient stories, twisted formations that looked as if they had been frozen mid-motion, and endless stretches of desert that disappeared into the horizon. There was a deep silence all around, broken only by the wind whispering through the dry brush.

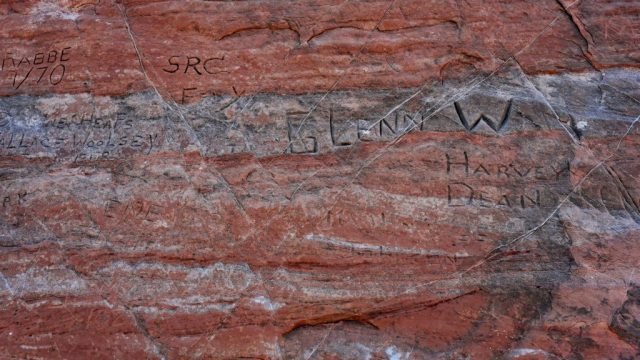

Passing the Lower Dry Creek, I stopped at the famous Dance Hall Rock, a place that carries both beauty and history. The settlers of the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition once gathered here for music and dancing. I could almost imagine the sound of fiddles echoing through the alcove, the laughter and steps of men and women celebrating under the sandstone ceiling. The rock itself forms a natural amphitheater — smooth, sheltering, and resonant. Its reddish curves catch the light like a sculpture, and standing there, I felt a quiet admiration for those who had crossed this unforgiving landscape with courage and faith. I parked my car and walked closer to the alcove, touched the cool surface of the rock, and silently paid my respect to the pioneers who once found joy here amid hardship.

Some miles later, I noticed a few cars parked near the roadside and decided to stop again. A man stood beside his car with his family — three kids running around in the sand. I asked him what there was to see nearby. He kindly explained the trails and then recommended another one, a few miles farther down the road. Following his advice, I turned onto Fortymile Spring Road.

At first, it looked promising, but soon the path began to descend sharply. The road turned rough and uneven, scattered with stones and deep ruts. I hesitated, remembering yesterday’s adventures, but curiosity made me drive a little farther. Then, sensing that it might get worse, I parked and decided to walk ahead. After about three hundred meters, I saw a mobile home leaning dangerously to one side, two wheels lifted off the ground, hanging in the air. No one was around. The sight sent a chill through me — the road was worse than I had imagined. I realized how lucky I was not to have driven farther. With my car, I would never have made it back uphill safely. It was time to turn around.

I continued toward the Hole-in-the-Rock, but the road there began to crumble and shake beneath the tires too. The surface became a washboard of deep grooves, and after yesterday’s challenges, I decided I had had enough adventure for now. Sometimes wisdom lies in knowing when to turn back.

On my return, I stopped again at Lower Dry Fork and decided to hike to the Peek-a-Boo Slot Canyon. The trail itself already offered spectacular views — wide stretches of desert opening into canyons, the distant cliffs glowing in warm tones of pink and ochre, their surfaces smooth as if polished by centuries of wind. The shapes were wild and strange, twisted into waves and arches, like frozen motion in stone.

Along the way, I met a family from Seattle. First, I spoke with the woman, who was walking a little behind the rest. She laughed when she told me about the rough road they had taken to get here — “horrible,” she called it. A few minutes later, I caught up with her husband, who turned out to be just as amused as I was. We soon discovered that they had taken the exact same road I had, but in a large truck with four-wheel drive and high clearance. He looked at me with disbelief when I mentioned I had come in a Toyota RAV4. “You did that road with that?” he said, shaking his head and laughing. “That’s crazy!”

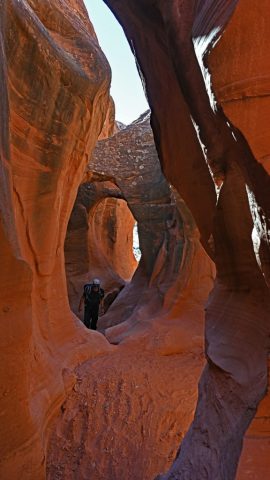

It felt good to share a laugh after the tension of the morning, and I was even more grateful when the man helped me climb the first and most difficult section of the Peek-a-Boo trail. The sandstone there is smooth and steep, and getting up the narrow entrance can be tricky without a hand. Once inside, the canyon enveloped me in its quiet mystery — the walls rising high and curving like ribbons of stone, glowing in shades of rose and amber. The light filtered through from above in narrow beams, painting the rock in soft, shifting colors.

As I stood there, surrounded by silence and stone, I thought again of the pioneers who once crossed this vast and wild country. Their endurance, their hope, and their spirit still seem to linger in the air, carried on the wind through these timeless canyons.

From the parking lot at Peek-a-Boo, I drove back along the dusty road toward the Devils Garden. The sun was high now, the air shimmering over the pale desert, and I could feel the heat pressing down even through the open windows. When I reached the Garden, I parked among a few scattered junipers and set up my small stove. Cooking lunch there, in the heart of that silent, sunburned wilderness, felt almost surreal — the red cliffs and creamy sandstone domes glowing around me like the walls of some forgotten temple carved by the wind.

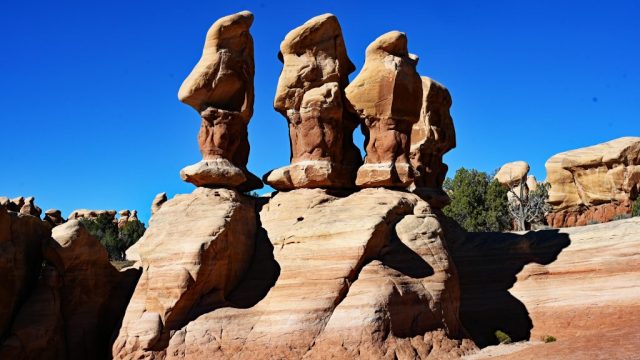

The Devils Garden Outstanding Natural Area is a secret world, tucked away from sight just beyond the Hole-in-the-Rock Road. From a distance, it looks like an ordinary stretch of desert, but as soon as I stepped into it, I found myself surrounded by a fantastic landscape of sculpted Navajo Sandstone. Delicate hoodoos — slender pillars crowned with fragile caps — stood like sentinels in soft shades of rose, apricot, and burnt orange. The smooth domes gleamed under the afternoon sun, their curves shaped by centuries of wind and rain. Narrow passages twisted between the rocks, opening suddenly into small clearings where tiny arches framed the blue sky. I wandered slowly through the labyrinth, touching the warm stone, feeling the grain of ancient sand that once was a vast dune field millions of years ago. The silence was deep, broken only by the whisper of the wind and the occasional cry of a distant raven. I took countless pictures, trying to capture the delicate play of light and shadow that turned the landscape into a living sculpture.

When I returned to the car, the air was beginning to cool slightly, and the long afternoon light had turned golden. I started north toward Highway 12 — the road everyone talks about, the one that cuts through some of the most dramatic scenery in Utah. I wanted to reach it near sunset, hoping for the kind of light that makes the cliffs glow from within.

My first stop was the Head of the Rocks Overlook, and it truly took my breath away. Before me stretched a vast panorama of undulating sandstone ridges, glowing in every shade from cream to deep red, with streaks of purple shadow filling the canyons. The Escalante Canyons rippled across the horizon, their walls folding and twisting like waves turned to stone. It felt like looking across a sea of rock frozen in motion.

A little farther along, I stopped at the Big Horn Canyon Scenic Overview. The view here was even more striking — the canyon dropping sharply below the overlook, its walls etched with layers of crimson and gold. The distant Henry Mountains rose beyond, their dark, rugged silhouettes contrasting with the pale desert in the foreground. It was the perfect spot to stand in quiet awe, feeling small before so much timeless beauty.

I continued on toward The Hogback, that famous narrow ridge of Highway 12 where the road clings to the top of a knife-edge spine, with steep drops on both sides. The view was astonishing, but the light was not kind. The sun was still fierce on the western side, bleaching the colors and casting harsh shadows. I waited for half an hour, hoping the light would soften, but it never did. Waiting until sunset wasn’t an option — I still had to reach Torrey for the night. So I drove on, the mountains glowing faintly in the rearview mirror as the evening light faded.

By the time I arrived at the Noor Hotel in Torrey, it was 8:30 p.m. The sky had turned a deep cobalt blue, and the last light lingered on the distant peaks of the Aquarius Plateau. I felt tired but deeply content — the kind of quiet satisfaction that only a long day on the open road, among such vast and beautiful landscapes, can bring.