6/7 February 2025

The area of Asti is marked by an extraordinary concentration of history. Well-preserved medieval family towers rise between Baroque churches and elegant palaces, bearing witness to a time when Asti was one of the most important commercial centers of northern Italy. Yet the city never feels loud or ostentatious. Its beauty reveals itself gradually, almost casually, as one wanders through its streets.

After checking into my hotel, I set out without any particular plan and let myself drift into the narrow lanes of the city. After only a few steps, I found myself standing in front of the Chiesa di San Rocco, an important example of Baroque architecture in Piedmont. Built between 1708 and 1720, the church reflects a restrained dignity. For centuries it was the seat of the Confraternita di San Rocco, a brotherhood formed after the devastating plague epidemic of 1630, when citizens gathered to seek the protection of Saint Roch, the patron saint of plague sufferers. Today, the church is regarded as a cultural jewel of Asti.

Not far from there, I encountered Spazio Kor, an interdisciplinary cultural space housed in the deconsecrated Baroque church of San Giuseppe. The former sacred space now serves as a venue for contemporary art, theatre, and civic engagement, creating a fascinating dialogue between past and present. A short walk later, I stood before the Palazzo di Giustizia, the modern courthouse. Its sober, functional architecture forms a deliberate contrast to the surrounding historic fabric.

Galery I – First impressions of Asti

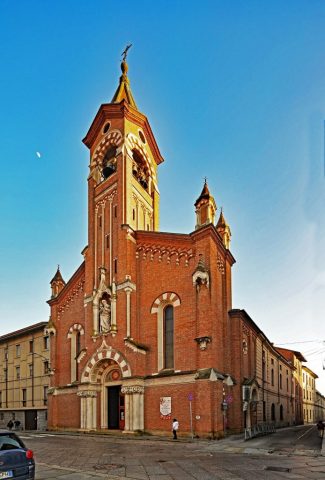

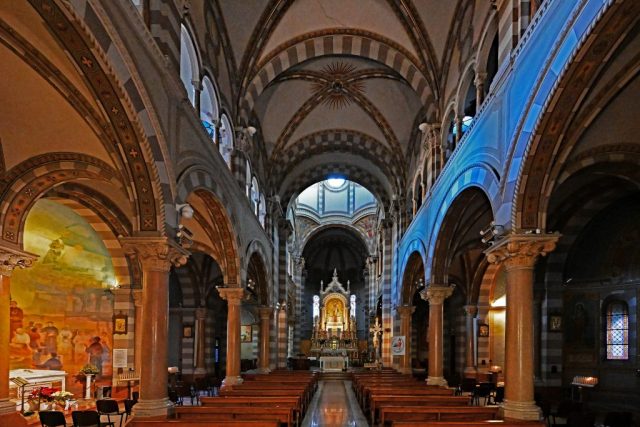

A small alley led me onward to the Santuario della Beata Vergine del Portone, one of the most important religious sites in Asti and today the diocesan sanctuary. The monumental structure was built beginning in 1902 and completed around 1912, enclosing an earlier small church as well as remnants of an ancient city gate. Designed in a Romanesque-Byzantine style, the building presents a modern yet imposing façade and occupies a prominent position on the edge of the historic center in the San Marco district.

Inside, the sanctuary reveals a solemn and harmonious atmosphere. At its heart is a fresco of the enthroned Madonna and Child from the 14th century, later reworked around 1500 by the renowned Asti painter Gandolfino da Roreto, who added the figures of Saint Secundus, the city’s patron saint, and Saint Mark. Baroque frescoes from the late 17th century adorn the vestibule above the altar, depicting scenes from the life of Mary. At the rear of the church stands a replica of the Grotto of Lourdes, while the extensive use of artificial marble lends the interior a ceremonial dignity.

Galery II – Santuario della Beata Vergine del Portone

From there, my path took me to Corso Vittorio Alfieri, where layers of history become visible at once. The Torre Rossa is especially striking in this regard. Its lower section dates back to the 1st century and has a sixteen-sided polygonal plan, while the upper cylindrical portion was added in the 12th century, when the tower was converted into a bell tower for the collegiate church of Saint Secundus — a function it still fulfils today. Alternating bands of terracotta and sandstone in white and red polychromy give the tower a distinctive Romanesque appearance typical of Asti.

Directly behind it stands the Chiesa di Santa Caterina, built around 1070 on the foundations of an earlier church and later rebuilt in the 18th century after the original Romanesque structure was demolished. The Baroque church features an oval central space surrounded by four chapels. Its brick-and-plaster façade is decorated with Corinthian columns and pilasters supporting a tympanum and a high cornice. The elliptical dome, rising 22 meters high and spanning 20 meters, dominates the interior. Four large arched windows illuminate depictions of Saints Peter, Paul, Francis of Assisi, and Joseph.

Galery III – Torre Rossa & Santa Caterina

Continuing along the Corso toward the city center, I passed the statue of Umberto I and soon found myself standing before the imposing Palazzo Alfieri, birthplace of the poet Vittorio Alfieri. Originally medieval in origin and owned by the Alfieri family since the 17th century, the palace was redesigned in 1736 by architect Benedetto Alfieri, Vittorio’s cousin. The façade reflects the characteristic Alfieri layout, with a series of windows on the main floor interrupted at the center by a grand portal framed by rusticated pilasters.

The inner courtyard of the palace is a true architectural highlight. Rather than being rectangular, it is trapezoidal, with side walls converging toward a concave rear wall. This perspective creates a dramatic, theatrical effect, as if the visitor were stepping onto a stage. Monumentality and scenographic elegance merge seamlessly here.

Galerie IV – Palazzo Alfieri

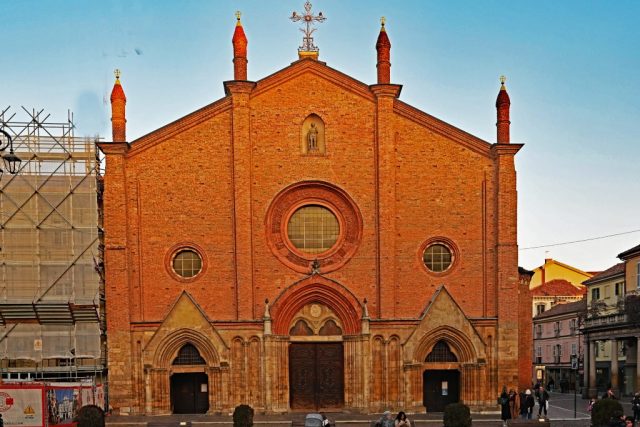

Opposite the palace stands the Santuario di San Giuseppe, whose warm red brick façade in the Neo-Romanesque style forms a lively contrast to the aristocratic elegance of Palazzo Alfieri. A striking feature is the monumental 3.6-meter-high statue of Saint Joseph, created in 1931 by sculptor Emilio Demetz. Designed by Monsignor Alessandro Thea and consecrated in the same year, the church features a central bell tower above the façade housing twelve bells. Inside, a vast columned hall unfolds, supported by forty columns. The floor is adorned with a richly patterned Cosmatesque mosaic. Particularly noteworthy are the altarpiece by Piero Dalle Ceste, depicting Saint Joseph with the Child, and the Marello Chapel, where the remains of Saint Giuseppe Marello, founder of the Oblates of Saint Joseph, are interred.

Galery V – Santuario di San Giuseppe

I continued along the street and paused at the corner of Via Roero to photograph the extensive complex of the Palazzi Roero di Monteu. Their appearance reflects a blend of medieval structures and later Baroque and Classical modifications. In Via Roero, typical features of Astigian Gothic architecture — brick construction and terracotta decoration — are visible, often updated in the 18th century with more elegant Baroque windows and balconies. Nearby lies Piazza dei Tre Re, once a center of power for the Roero and De Regibus families.

From here, the Torre De Regibus came into view at the junction of Via Roero and Corso Alfieri. Built in the 13th century in Gothic style, it is the only surviving tower in Asti with an octagonal ground plan. Originally about 39 meters tall and crowned with Ghibelline battlements, it lost its upper three floors in the 18th century and now stands at approximately 27 meters. The tower once formed part of a defensive complex belonging to the De Regibus family, known collectively as the “Tre Re”.

Across the street stands the Liceo Classico Vittorio Alfieri, founded in 1860 and named after the poet in 1865. The present building rests on the foundations of the former Sant’Anastasio complex and contains an important Lombard crypt.

Turning into Via Giovanni Giobert, I stopped before the Torre Solaro, one of the most prominent medieval family towers in Asti. Built around 1350 in the Piedmontese Gothic style, the tower belonged to the powerful Solaro family, deeply involved in the city’s internal power struggles. Constructed primarily of brick, the tower rises with restrained elegance and reflects the ambitions of its former owners.

Galery VI – Towers and power in medieval Asti

I eventually reached Piazza Roma, dominated by the Palazzo del Podestà, one of the best-preserved medieval palaces in the area, dating back to the 13th century. With its cross vaults on the ground floor and brick-and-sandstone façade, it exemplifies a fortified medieval residence. Once the seat of city administration, it now stands as the last remnant of a larger historic complex. Behind it rises the Comentina Tower, integrated into a 20th-century palace and adorned with Ghibelline battlements. Opposite stands the Monumento all’Unità d’Italia, erected in 1898 to commemorate Italian unification.

Galery VII – Piazza Roma

I turned into Via Giosuè Carducci and then into Piazza Giovanni Goria, where the Torre Troyana soon appeared in the distance. Acquired by the Troia family around 1250 and raised by three additional floors, the tower was later integrated into the Palazzo Ducale in the 14th century. Its square plan, well-preserved swallow-tail battlements, and elegant biforate windows make it a defining example of medieval urban architecture. Once a symbol of power and later a bell tower, it is today one of Asti’s most recognizable landmarks and a popular viewpoint.

Directly behind it lies Piazza Medici, one of the city’s oldest squares. The Palazzo Medici, dating back to the 13th or 14th century, reflects the medieval practice of demonstrating power through towers and fortified buildings. Its current, castle-like appearance dates from extensive renovations at the end of the 19th century, commissioned by Luigi de Medici. At the center of the square stands the Fontana dell’Acquedotto di Cantarana, built to celebrate the city’s first modern aqueduct. Until the late 19th century, Asti relied on private wells and cisterns.

At the corner of Via Pietro Gobetti and Corso Vittorio Alfieri stands the Palazzo Gastaldi, built around 1898. A fine example of Liberty style (Italian Art Nouveau), the building today houses the headquarters of the Consorzio Barbera d’Asti e Vini del Monferrato.

Galery VIII– Piazza Medici & Surrounding

Not far, I find myself standing on Piazza San Secondo, a place where history feels almost physically present. The Collegiata di San Secondo rises before me with a quiet dignity that seems to extend far beyond its walls. This is the very spot where the Roman soldier Secondo is believed to have been executed and buried as a martyr in the year 119 AD. The thought alone lends the square an atmosphere of reverence and stillness. Although the earliest written references to a church here date back to the year 880, construction of the present building did not begin until 1256. Even so, the church feels as though it has always belonged to this place.

As I draw closer, the warm glow of the red brick immediately catches my eye, a defining feature of Piedmontese Gothic architecture. Pointed arches articulate the structure, and the façade—completed around 1462—stands out with its three richly decorated marble portals and a central rose window. In the fifteenth century, the church was extended by one bay toward the square, giving it a sense of gentle expansion. Particularly striking is the imposing bell tower from the tenth century, a remnant of the Romanesque predecessor, which, together with parts of the crypt, reveals the deep historical layering of this site. A major restoration carried out between 1968 and 1974 restored the church’s medieval character while preserving the patina of centuries past.

Right next to the church stands the Palazzo Civico, its pale, almost creamy façade forming a fascinating contrast to the dark red brick of the Gothic basilica. The building acquired its current Baroque appearance between 1726 and 1730, yet its foundations rest on much older medieval structures. Once home to the Curia communis and later the Palazzo del Popolo, it became the seat of the Podestà at the end of the fourteenth century. As I study its balconies and rhythmically arranged windows, I am reminded of how deeply civic pride and political authority are carved into the stone of this city.

Gallery IX: Collegiata di San Secondo and Palazzo Civico

From here, I follow Via C. Benso di Cavour toward Piazza Statuto. The route leads me straight into the medieval heart of Asti. Soon I am standing in front of the Palazzo degli Antichi Tribunali, a thirteenth-century building constructed entirely of brick. Its austere appearance reflects its original function: this was the seat of judicial proceedings and, most likely, also of prisons. The atmosphere feels dense and heavy, as though the voices of past trials are still embedded in the walls.

Piazza Statuto opens up before me, lively and spacious. Here rises the Torre Guttuari with its adjoining palace. The Guttuari family once owned several buildings overlooking this square, which was formerly known as Piazza delle Erbe and served as one of the city’s marketplaces. I imagine the bustle and commerce that once filled this space. To the right of the tower stands a late-nineteenth-century building, a fine example of eclectic architecture with strong Neo-Renaissance elements. Built around 1890, it served as a residence and as the headquarters of the Banca Agricola Astigiana. Its richer ornamentation and lighter tones create an engaging contrast with the surrounding medieval structures.

Gallery X: Piazza Statuto

Just a few steps further along Via XX Settembre, I find myself standing in front of the Chiesa della Conversione di San Paolo. Built between 1787 and 1794, this Baroque church blends harmoniously into the historic cityscape. Its gently curved forms and balanced façade radiate a quiet elegance. It was constructed to replace an older church, parts of which were incorporated into the new building, and it stands as an important example of late Baroque architecture in the region.

Immediately beside it, I discover the Ex Chiesa di San Paolo, whose story feels even more complex. Originally built in the thirteenth century as a three-aisled church, it underwent numerous transformations over time. The entrance was once located on the opposite side before being relocated next to the Romanesque bell tower. Parts of the apse were later incorporated into the Church of the Conversion of Saint Paul. In the twentieth century, the building was deconsecrated: the right aisle was demolished to create the Piazzetta di San Paolo, while the left aisle was integrated into a residential building. Today, the former church houses a shop—an evocative example of how history evolves while remaining visible.

Image Gallery: San Paolo

As I continue my walk, I repeatedly encounter sections of Asti’s medieval city walls, the Cinta muraria di Asti. Their origins date back to around 89 BC, when Asti was still the Roman city of Hasta Pompeia. One particularly striking remnant of this era is the base of the Torre Rossa. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at the height of Asti’s prosperity as an independent commune and major trading center, the fortifications were significantly expanded. Around 1340, Luchino Visconti ordered the construction of a second ring of walls to protect the newly developed suburbs. These fortifications speak of power, wealth, and the constant need for defense.

Among the most distinctive family towers in the historic center is the Torre dei Natta, built at the end of the twelfth century. Originally standing as an isolated structure, it was later incorporated into a larger palace complex. Its square ground plan, slightly tapering silhouette, and crowning frieze of double, droplet-shaped hanging arches give it a strict yet elegant appearance. As a fine example of Asti Gothic architecture, the tower remains a defining feature of the cityscape.

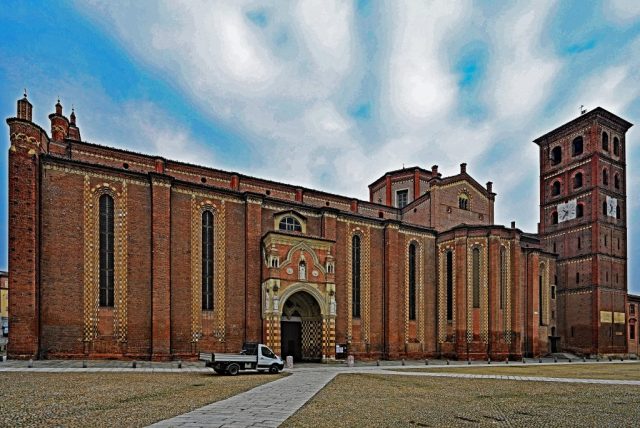

Eventually, I arrive at the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, the most important religious building in Asti. Even from the outside, its scale and the harmonious combination of red brick and light sandstone are impressive. The earliest predecessor structures date back to the fifth or sixth century. A Romanesque church, consecrated by Pope Urban II in 1095, later partially collapsed or was damaged by fires. The present cathedral was largely constructed between 1327 and 1354, while the Romanesque bell tower had already been completed in 1266.

The Gothic design of the three-aisled basilica clearly emphasizes verticality, lending the building an almost weightless monumentality. The magnificent Gothic side portal immediately draws my attention. Inside, the contrast is striking: while the exterior appears relatively restrained, the interior is richly decorated with eighteenth-century frescoes, including works by Carlo Innocenzo Carloni. Measuring 82 meters in length and rising 24 meters high, the space unfolds with breathtaking grandeur. Artworks such as the fifteenth-century baptismal font and the splendid altars make the cathedral one of the cultural highlights of my journey.

Image Gallery: Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta

As I left Asti after two days, I had the feeling of having walked through a city that doesn’t display its history, but lives it. Towers, bricks, frescoes, and squares combined to form a quiet, impressive narrative – a city that reveals itself. An attentive walker experienced, how past and present intertwine here in a truly remarkable way and whose effects linger long afterward.