6 July 2016

After breakfast we left Gardiner and drove south through Mammoth, following the road deeper into Yellowstone. The morning light was clear and warm, and the mountains still carried a quiet freshness, as if the day had only just begun to breathe. Along the way we stopped again and again, because Yellowstone never allows one to simply pass through. Calcite Springs Overlook, Tower Fall, and Devil’s Den each asked for our time, and we gladly gave it. Wildlife slowed us down as well, and we welcomed every pause, every moment when the landscape demanded our full attention.

Calcite Springs Overlook was reached by a short walk along a wooden boardwalk with stairs. Standing there, we looked down into the northern end of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Upstream, the Yellowstone River cut deeply into the earth, carving a rugged and steep canyon whose dark rock walls rose sharply from the water. On the opposite side, the geology revealed itself in striking columnar joints, stone pillars standing like an organ carved by fire and time. Downstream, the scene changed completely. The hillside of Calcite Springs appeared bleached and barren, scarred by hydrothermal activity, with steam rising quietly from vents in the ground. The canyon walls were sharply notched and dramatic, and as we looked up, we could see birds of prey circling high above, using the updrafts along the cliffs, their silhouettes moving slowly across the sky.

A short drive brought us to Tower Fall. The waterfall plunged 132 feet into the canyon below, a narrow white ribbon dropping straight down against dark volcanic rock. It was easy to imagine the impact this sight must have had when photographer William Henry Jackson and painter Thomas Moran brought their images of Yellowstone, including Tower Fall, back to Washington in 1871. Those pictures helped convince Congress to protect this landscape forever, and standing there, we felt connected to that moment in history, when beauty changed the fate of a place.

We continued past Devil’s Den and finally reached the parking lot for the Mount Washburn Trail. This was the main goal of the day: a hike of 11.4 kilometers with 428 meters of elevation gain, leading to one of the most panoramic viewpoints in Yellowstone.

Gallery I – Along the Road to Mount Washburn

The Mount Washburn Trail is one of the most popular hikes in Yellowstone, and for good reason. From the summit at 10,243 feet (3,122 meters), the views stretch across vast parts of the park. The trail can be reached from Dunraven Pass or Chittenden Road, and although it is well maintained, it gains elevation steadily and demands respect, especially at altitude. Wildflowers often color the slopes in summer, and bighorn sheep are sometimes seen along the ridges. At the top stands an historic fire lookout, complete with exhibits and even restrooms, a small but welcome shelter in such an exposed place.

We hiked the trail on the 6th of July 2016, together with our son Simon. Shortly after starting, we encountered a small squirrel, busy with its meal, completely unconcerned by our presence. Apart from a few birds, it was the only wildlife we saw on the trail that day, but the scenery more than made up for it. The path climbed steadily, and with every turn the views opened wider.

At first the weather was kind. Sunshine illuminated the slopes, bringing out greens and muted golds in the grass, and the distant mountains appeared soft and blue. Then the sky began to change. Clouds thickened and moved in quickly, the light flattening and cooling. A strong wind rose, cutting through our jackets and reminding us how exposed this mountain really was. When we finally saw the building on the summit ahead of us, it felt like a promise of warmth and shelter. The trail twisted upward in long curves, and the wind grew stronger with every step, pushing against us and making the final ascent feel harder than the distance alone would suggest.

Gallery II – Climbing Mount Washburn

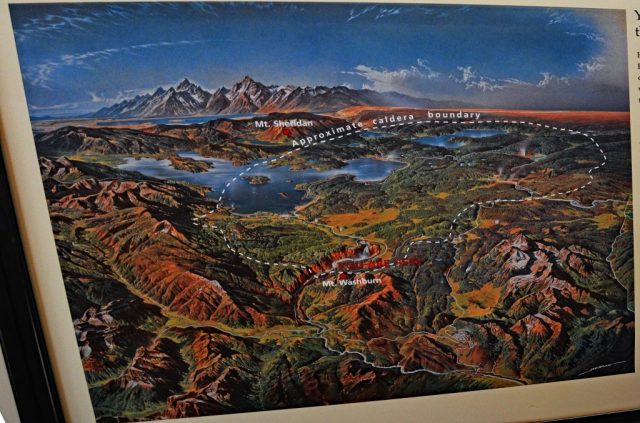

At the summit we entered the building immediately, grateful for the chance to warm up. Inside, displays explained the landscape spread out below us. One image showed that from Mount Washburn we could see as far as Mount Sheridan, 37 miles to the south. Between these two peaks lies the Yellowstone caldera, the immense volcanic crater formed by a catastrophic eruption around 640,000 years ago. That explosion was more than a thousand times larger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, a reminder that the peaceful scenery around us was shaped by unimaginable force.

Once we felt warm again, we stepped back outside. The wind was still fierce, but the views were irresistible. Valleys opened in every direction, shaped like wide bowls and sharp V’s, carved by ice, water, and time. The colors were subtle but powerful: deep greens in the lower forests, gray and brown rock faces higher up, and distant mountains fading into pale blue and white under clouds and patches of sun. We took photos, including one of us standing by the sign marking the elevation of 3,122 meters, the vast Yellowstone landscape stretching out behind us.

Gallery III – On the Summit of Mount Washburn

The descent was quieter. The wind still pressed against us, and the air remained cold, but we had time to absorb the scenery again, now from a different angle. The valleys seemed deeper on the way down, the mountains more massive, their shapes clearer as the trail slowly unwound back toward the parking lot. It had been a hard hike, made tougher by the weather, but it was worth every step. Mount Washburn had shown us Yellowstone in all its scale and mood, from gentle sunshine to raw alpine wind, and it remained one of those places that stays vivid in memory long after the trail ends.